Bright World: Jane Gottlieb

Jane Gottlieb loves color. So much so that just about everything in her life is vivid, bright and intensely colored—from her clothes, cars and furniture to the interior and exterior walls of her Santa Barbara home.

The colors in her wardrobe like the colors in her photography are saturated and eye-catching, but make no mistake, her artistic work is not a trove of psychedelic stoner posters, they’re images steeped in the intersection of painting and photography and markers of the evolution of analog to digital image-making. They also embody an earnestly Californian vision of leisure, landscapes, car culture and monuments.

“Emerging in the late 1980s as a significant addition to the development of West Coast photography, Jane Gottlieb’s work sounds a varied yet subtle coda to the concerns of the Los Angeles art scene that prevailed from the late 1960s to the mid1970s,” writes Laguna Art Museum’s late chief curator Michael McManus in an introduction to the exhibition catalogue for Gottlieb’s first big show in 1988.

Jane Gottlieb, Cadillac Fin

Originally from Los Angeles, Gottlieb studied painting and art history from 1964 to 1968 at UC Berkeley, University of Syracuse in Florence, Italy and UCLA. She then studied graphic design at School of Visual Arts in New York City, launching a career in advertising that culminated with Gottlieb owning her own agency in Los Angeles. At 35, Gottlieb landed the Laguna show, left the ad business and started working fulltime as an artist.

Her early series on LA’s car culture led to further photographic collections of swimming pools, gardens and architecture. Gottlieb composed classical vignettes of Southern California living that pushed the viewer’s perspective, often using a fisheye lens to further distort and embellish reality. She traveled the world with her SLR and catalogued thousands of images. Then, Gottlieb discovered a process to alter color on film that over the next four decades she’d develop into her signature and bridge from analog to digital photography.

In the seventies and eighties, Gottlieb captured images with Kodachrome 35mm color slides that she printed using the Cibachrome process that was archival and could produce saturated colors. Inspired by the retouching process in which she observed a master printer spot her prints with dyes, adding color where there was no color, she began painting multiple layers of dyes into her photographs. By pushing the color into the emulsion, it would dry into the glossy luminescent photographic print with unrealistic, saturated colors.

Jane Gottlieb, California Pool

Gottlieb’s palette was sown in her studies of Fauvism, travels to Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula and the feathers of her beloved parrot Adler; and her collages and transposed colors are rooted in Surrealism as well as the artist’s uncommon optimism and playfulness.

“Color shifted the reality of the photography,” says Gottlieb, who notes that she was among the first to experiment with this technique. “It was difficult because it was easy to scratch and it was hard to saturate the color into the emulsion, you had to repeatedly paint it.” There was also the expense. Thirty years ago, printing a 30 x 40-inch print cost $500, recalls Gottlieb.

For the next 15 years, Gottlieb painted on her Cibachrome prints, but by 1991, she was also using Photoshop. While she was ready at the launch of Photoshop 2.0 to transition to digital, the art world was not. The Nancy Hoffman Gallery that represented her in New York in the nineties would only show her handpainted photographs.

Jane Gottlieb, Disney Hall, test print

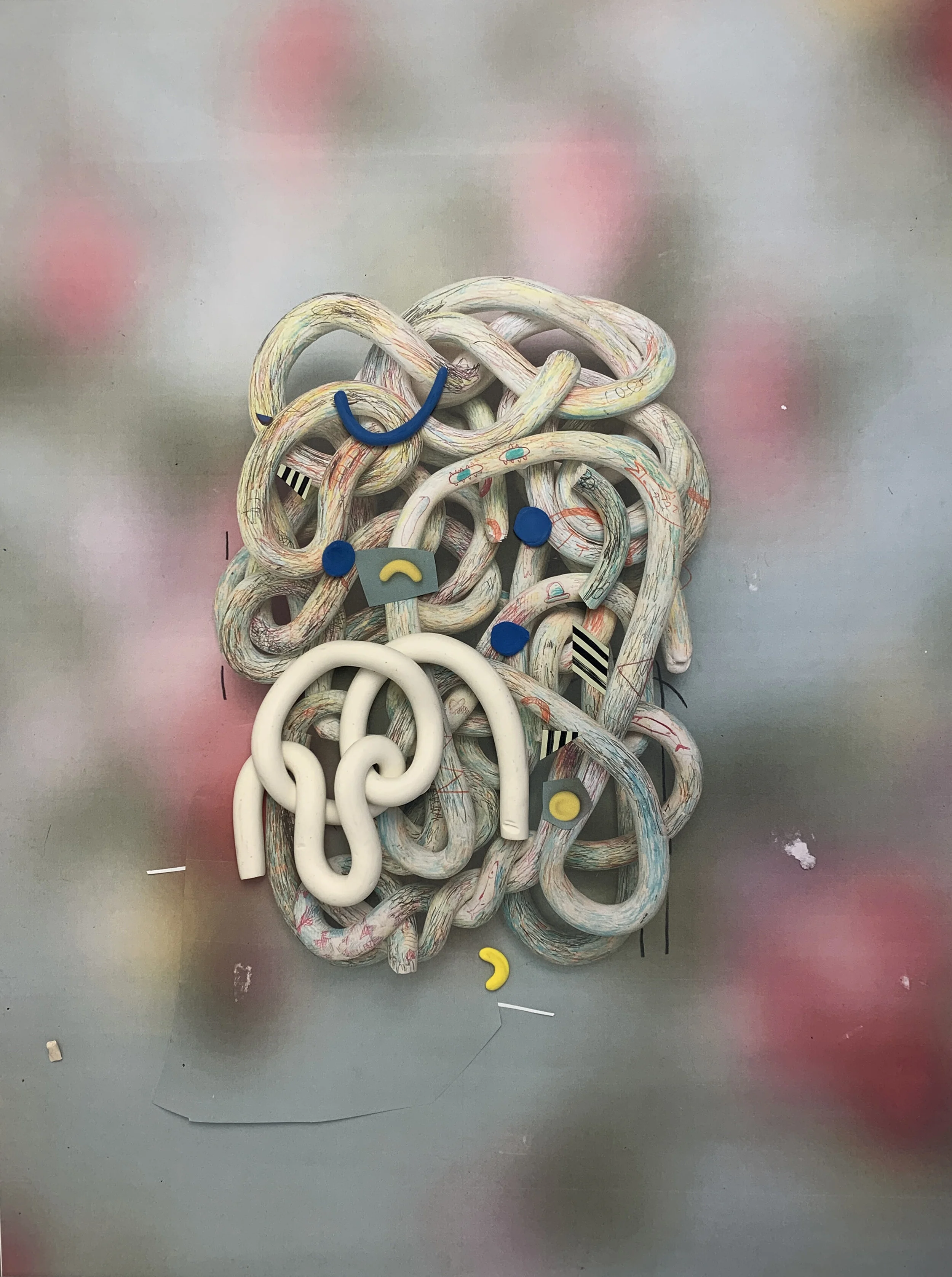

Jane Gottlieb, Untitled

Today, Gottlieb uses Photoshop to create new work, often pulling from her inventory of original slides dating back to her twenties, or digitally enhancing her handpainted color prints. Her most recent pieces are dye sublimation prints on aluminum that she has printed by master printer Eric States of Photo Printing Pros in Goleta. The works are archival and can be cleaned with Windex.

Gottlieb’s artworks are now on view at UCLA across six buildings. At UC Santa Barbara, Gottlieb’s work is exhibited in five buildings, including the permanent collection of the Art, Design and Architecture Museum and a 14 by 15 feet piece in the Library.

Jane Gottlieb, UCSB Library

This article was originally published in Lum’s Winter 2021 print magazine.