Can Landscape Be Contemporary? • 22 Miles: Ojai Valley Landscapes

By Tom Pazderka

22 Miles: Ojai Valley Landscapes was co-curated by two well-known landscape artists, Jennifer Moses and Gail Pidduck. The title of the Ojai Valley Museum exhibition refers to the distance between their studios on opposite sides of the valley. I went to the museum for two reasons, first to see this exhibition since I like landscape painting, though granted I know the subject to be fairly straightforward, and second to gather some information about the museum (OVM) and because I just became an Ojai transplant and wanted to learn a little bit about the local arts community.

I went in blindly, as I usually do when I see art exhibitions. I typically don’t like the work or the show to be explained to me in advance. This tends to ruin my own experience of the work and the meaning, if there is any to be had, behind it. It is through confronting the work straight on that I can let the meaning emerge through contemplating the work and running it through the filter inside my own head. Eventually meanings do emerge, often some answers to very cryptic answers arise, but mostly more questions come up that may or may not have satisfactory answers. Here is one of them.

ABOVE: Jennifer Moses, “Solitude”; Steve Curry, “Ojai Foothills”; Gail Pidduck, “Koenigstein”

What does it mean to be contemporary? Is it simply the now, the shiny surfaces and kitschy detritus of a verdant society, the half-baked ideas of the also-conceptualists? Much of contemporary art tends to resist the notion of the contemporary, opting for specific systems and tactics that magnify their resistance, so that they may become and remain—to borrow a well-worn Nietzscheism—contemporary, all too contemporary. Action/reaction, positive/negative, active/passive—all activity is duly absorbed into the system that thrives on attention, spectacle and fame. Under such conditions Barack Obama becomes president for appearing as a symbol or icon of all that is decent, reasonable, inclusive and worldly. Donald Trump becomes president for exactly the opposite reasons. Both the enigmatic metaphors of Obama and Trump are subsumed in the concept of the contemporary and move beyond the world of politics into other worlds, including the art world.

Landscape painting seems to actively resist the idea of contemporary for another completely unrelated reason. It may be style, since all artists included in the show 22 Miles have different styles, but they are not unique in the real sense of the word. All works included in the exhibition are oil or pastel, most are on linen or board, and all are absolutely and resolutely wedded to a conservative notion of representation—lots of color, classical painting styles, tried and true vantage points, little experimentation—as if the idea of resistance came not from a place of activity but of conscious interpassivity. Some opt for abstraction, but in the sense of the landscape as the ultimate phantasmatic subject, that almost all landscape painters seem to desire to escape into—the landscape itself becomes an abstraction, devoid of all human interaction or inclusion.

What we get is a formalist abstract landscape, empty of all its despoiled aspects. No trash, no objects, just a chair or building here and there, suggesting human presence but staunchly reactive to it. In this sense, the landscape painting is absolutely not contemporary, and this is a good thing in my opinion. It resists dealing with human leftovers and subjectivity, opting for a lofty ideal in the form of shape and color. Yet, the landscape painting remains an entirely contemporary subject just for this same reason.

Dan Schultz, “Ojai Valley Orchard”

There are endless versions and run-ons in the world of landscape art, done by very contemporary artists, some of whom live in this region. 22 Miles sits more on the conservative side of the fence, but the show is nonetheless striking and beautiful, each painting like a small window into another world out there somewherewhich is primarily in fact here, in and around the Ojai valley. So well made are most of the paintings that one tends to forget the interpassivity at play here. On seeing the paintings, one gets the sense of satisfaction that one does not need to actually go outside and see the landscapes depicted, even though they’re right here. The artist sees for us; or perhaps, even further, the painting is what sees, instead of us.

I live in Ojai now and it is easy to understand why the landscape around here has such an effect on the people that live and have lived here. The landscape surrounding Ojai is like a painting in the real, one that we can enter and get lost in on a simple drive along Highway 33. What the landscape painting and the artists in 22 Miles try to embody is this piece of the real experience as an abstraction—a quasi-religious experience of inner subjectivity. In other words, the paintings are themselves attempted substitutes for the real emotional impact incurred when one is confronted with some form of overwhelming experience of the natural world, standing on a mountain top, prolonged listening to a bubbling brook or waterfall, the shuffle of leaves or wind blowing through mountain pines.

Yet there is another abstracted notion at play here, one that put the Romantic and the Hudson River painters at odds a long while ago. Many contemporary landscape painters pay homage to these similar, but rather disparate schools of painting. But whereas the Hudson River painters painted in order to elevate landscape to a higher form of expression, to show the grandeur and the sublime elements of the natural world in its unattainable beauty, epic and awesome, some of the Romantics like Caspar David Friedrich did everything in their power to subvert this simplified form of painterly ideology, and used landscape and the people within it to question the notions of our belonging to or within our environment. While Hudson River painters sought to dominate nature in some ways, Friedrich saw humanity as ambiguously relating to nature via a complex emotional response, from awe to fear, depending on context and circumstance.

Mark Kerckhoff, “Citrus Grove Near the Old Bridge”

A spectrum of emotional responses can be at play all at once. One can be awed by the sight of a tornado or volcanic eruption, but also in absolute terror of the same if one is close enough and in real danger of those elements. Similarly, the causal hiker or landscape painter may go through a gamut of emotions on a two-hour outing from relaxation, reflection and peace to anxiety within a matter of moments. These experiences are irreducible to words or even pictures.

But to return to belonging, the exhibition’s lack of human presence seems to suggest that one does not belong to or in nature—nature is dangerous, inhospitable, highly seductive and symbolic. The painting is a vignette of the idealized form of nature as nurturing and caring, a cozy retreat. While the reality can be the exact opposite, just picture a beautiful, snow covered rocky mountain peak and then understand that the apparent serenity of this image belies the frigid, brutal conditions, freezing temperatures and pounding winds. In this exhibition, however, one can imagine oneself laying down in the fields and meadows before the mountain ridges, as if on a fluffy pillow with a rolling sky above, the shadows dancing across the grizzled mountain faces of the Ojai peaks.

But there is contemporariness in the idea of landscape painting, in the act of painting a landscape, and in the painting itself. Despite its marriage to a sort of conservatism and pious deference to the natural world, its worship of John Muir and a canon of environmentalists, landscape painting has the capacity to affect the brain, the mind and the soul. My critical look at the contemporariness of landscape painting belies the fact that I am a big fan of great landscape art, the painterly and the conceptual kind. I am mostly critical of the things that I like the best, just so the reader understands.

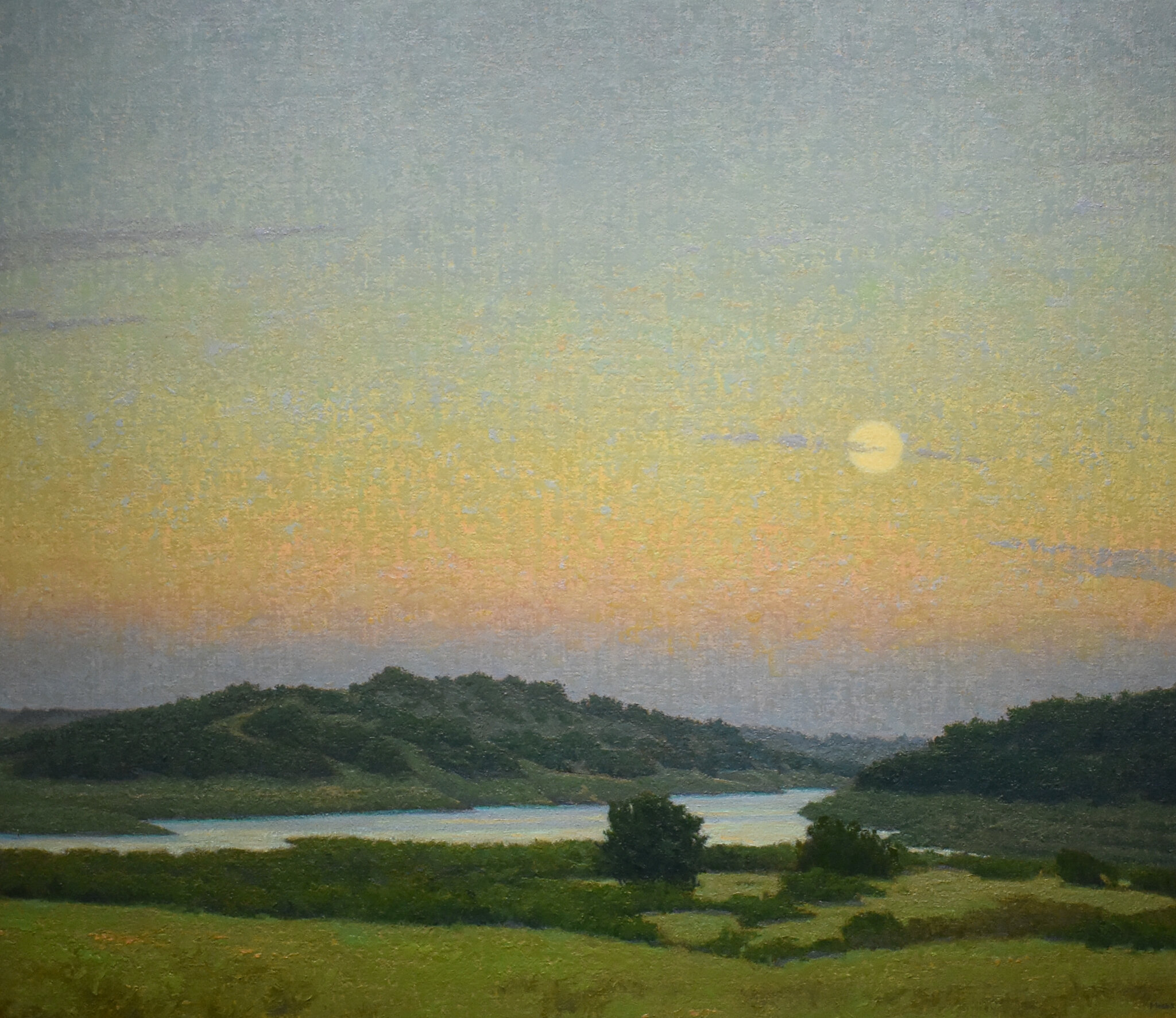

Bruce Everett, “Lake Casitas”

Of the many works in 22 Miles, several artists engaged the notion of the contemporary or a ‘way into’ the setting that moves beyond illustration of the simple landscape painting, whether it’s line, color, technique, style or something entirely different. Mark Kerckhoff, Gail Pidduck and Rick Garcia all painted works whose style reminds me of computer generated graphics or video games, realizing in paint a graphical style of games like Firewatch, in which players interact with a landscape environment in full 3D, that is rendered both realistically and like an illustration.

Pidduck’s use of outline diverges somewhat from the rest of the artists. It is a tactic that is used well and doesn’t get in the way of the image while subtly highlighting rocks and trees. The colors of Bruce Everett also suggest this interplay between real and unreal, the abstract and the concrete. His painting is perhaps closest to the graphical effect of Firewatch. Flattened space, exaggerated color choices, and an utterly realistic image are the central tenets of this style.

I won’t go into the idea of the sublime for obvious reasons—this is not an exhibition that engages the audience at that level—but the artsists that present us with the notion of the grand or spectacular are Steve Curry, Dan Schultz, Arturo Tello and Jennifer Moses, each painting sitting on the shores of awe inspiring quietude, a moment’s inspiration that can be unsettling if one chooses them to be.

22 Miles: Ojai Valley Landscapes includes work by Meredith Brooks Abbott, Robert Abbott, Whitney Abbott, Jannene Behl, Susan Cook, Steve Curry, Karl Dempwolf, Bruce Everett, Rick Garcia, Whitney Hansen, Connie Jenkins, Mark Kerckhoff, Eric Merrell, Jennifer Moses, Susan Petty, Gail Pidduck, Ian Roberts, Dan Schultz, Arturo Tello, Elizabeth Tolley and Anne Ward. Ojai Valley Museum, 130 W. Ojai Ave.

COVER ART: Rick Garcia, “After the Rain”